If you had told me a few years ago that I would be spending a large portion of my free time collecting litter, recording litter, speaking or writing to friends, family, and politicians about litter, and reading newspaper articles about litter with the same rapt attention that some people dedicate to sports or fashion, I would have said, “Rubbish!”

But here we are, at the start of 2016 and most of the time outside my day job is dedicated to learning about litter and trying to come up with ways of stopping it. The timing, I admit, was fortuitous: I got involved as litter began to hit the news, with journalists deploring the state of the UK, and celebrities like Kirstie Allsopp and Jeremy Paxman lending their voice to the clamour for a cleaner community, countryside, and coast. I even spent a Friday evening watching the Parliamentary Litter Inquiry in January 2015 and thought this was it—the UK was going to wake up to its litter problem, take the different suggestions into consideration, and do something about it.

But no. Instead, it has led to a recent announcement that the government is going to create a national litter strategy. Which raises the question: what have they been doing over the past year (or the past ten for that matter)? Shouldn’t the preliminary research be done and a plan already drawn up? And my biggest concern: having a national litter strategy is not the same as acting on it.

Which brings me to the title of this blog entry. I have spent the past year thinking about the litter problem–after all, a rubbish walk gives you plenty of time to observe what’s happening in a community and to think about ways of solving it. I know I am not the only person or organisation making these suggestions: a quick Google search will reveal a great deal of “litter”-ature about human behaviour and litter reduction. The Parliamentary Litter Inquiry in January 2015 saw people speaking about litter and sharing their thoughts for potential solutions more widely. But that last piece of the puzzle, actually acting upon the ideas that have been generated? I have yet to see any indication that it is ever going to happen. Instead, it feels like we’re stuck in a Groundhog Day scenario of repeating the first two options ad infinitum. Of course, this isn’t to say that the government should act recklessly or throw money in different directions to see what sticks, but rather research the options available, put together a plan … and act on it.

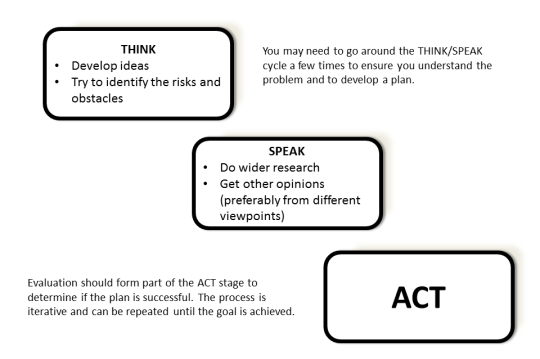

Think, Speak, Act: Scoping, planning, and implementation cycles are obviously a key part of project management the world over; however, with litter at least, that vital final stage appears to have been overlooked.

I feel that this is being made far harder than it should be. There are a lot of problems that are tricky to solve: flooding, funding the NHS, climate change. But littering is something that is literally in our hands; it is caused by us and therefore can be solved by us. After all, littering is not a universal problem; other countries have managed to tackle this–what are they doing right that we are getting so very wrong?

First, I think it’s recognising that there is no one solution or magic bullet to make the problem of litter go away. The country has gotten to the point where there is no quick or easy fix, and, like most things in life, it will take time, effort, and money if it is to be done properly. But to save those working on the strategy a bit of time, here is my general manifesto for tackling litter in the UK:

1. Take it seriously: My personal belief is that one of the reasons we have gotten into the state we’re in is that litter is seen as a low priority. Lives aren’t immediately at risk (although the RSPCA reports 5000 calls of wildlife or pets injured by litter each year), and, well, it’s waste. No one really likes to think about waste or what happens with a product once they’re done with it. There is an out-of-sight-out-of-mind mentality that needs to be addressed, both as regards to litter and the waste of finite resources in general.

2. Be willing to do things differently: The oft-quoted definition of insanity is “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”. This seems to be the current situation with litter prevention, coupled with the failure to grasp that what has worked in the past does not necessarily work now. This is applicable from awareness-raising interventions to the location and size of bins in a modern, urban environment.

For example, while poster campaigns, television adverts, and newspaper or magazine articles all have their place, people consume media in so many different ways today. A message that captures the attention of one segment of the audience will completely turn another off—if they even notice it at all. We must be willing to drill into what will work for different members of the public, and be aware that a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be effective.

Following on from this is recognising that patterns of consumption have changed over the past several decades, as has the amount and prevalence of packaging. A food-on-the-go culture seems to be here to stay. Because the context has changed so drastically, shouldn’t the interventions launched also take such changes into account? This may mean a new and improved binfrastructure, requiring businesses to take on additional responsibilities, or rethinking how recycling is handled.

3. A united effort: One of the problems with litter management in the UK is that so many different authorities are responsible for many so many different aspects—or think that someone else is responsible. As a result, much of the rubbish falls between the cracks, both metaphorical and literal. This is true for waste management as well as awareness campaigns and other initiatives that tend to have a local focus. Instead, imagine a campaign that hits everywhere in the UK at once: it’s on television, in the newspaper, on bus shelters and buses, in schools and youth groups, online … everywhere you turn, the message gets across: littering is no longer acceptable. Yet keep in mind that any messages need to be reinforced: it’s not enough to produce a shiny campaign or intervention that is trialled for a year then disappears. A positive anti-litter message needs to become part of the national culture, constantly and consistently touched upon.

4. Cleaning is not litter prevention: An annual volunteer “Community Clean Up” is often pointed to by the government as a sign of action. As someone who regularly picks up litter and helps organise a monthly clean up, I wholeheartedly agree that such cleaning is absolutely necessary if we want to avoid living in a littered environment. Cleaning can also serve to open a dialogue with members of the community as well as draw attention to the problem.

But this is not litter prevention. Such clean ups make an area look nice (for a time). They make the volunteers who did the cleaning feel good and provide great photo ops for politicians (both sets of people who are unlikely to litter in the first place). They are quick and cheap in comparison to implementing a plan to change behaviour. But isn’t it time to focus on the cause of the issue–people who litter–rather than strictly dealing with the symptom?

5. Be aware of individual mindsets and social norms: This brings me to the final point and hints at why stopping litter once the habit is entrenched can be difficult (it also underscores the point above: cleaning is not litter prevention).

Stopping litter requires completely changing the mindset of a not-insignificant number of people. Littering is not just about laziness as commonly claimed, but can also be due to illogical, but deeply ingrained beliefs. For example, two related opinions regularly crop up in the discussion surrounding litter: some think that because they pay their Council Tax, they therefore pay for someone to clean up after them. In turn, others think that littering makes a paying job for someone; keeping someone in employment is positive and so littering isn’t a problem. There is the failure to recognise that money spent on cleaning up litter could instead be spent on other things: education, NHS, infrastructure. As Councils’ budgets are stretched to the limit, wouldn’t it make more sense to deploy people where they are actually needed, rather than have them carry out a job that shouldn’t need to be done in the first place?

Capitalise on power of social norms: make it normal to use the bin. Ensure that there is a social consequence for littering. Make not littering an ingrained behaviour. Littering is often the first sign that an area is uncared for, allowing other anti-social behaviours to flourish. Imagine the changes we could have in our community by starting from the ground up.

Going even further, here are some specific suggestions for things that could be done. If everyone, from government policy makers to businesses to individuals within the community shouldered just a little of the responsibility, we stand a chance of not only cleaning up the country, but keeping it that way. However, rather than a pick-and-mix approach, a holistic system needs to be put in place if there is any hope of actually turning the tide.

GOVERNMENT

As an individual, there is a lot I can do to fight litter within my own community, from picking up rubbish to running educational programmes. Yet ultimately, the government must get involved if it is serious about stopping the problem. These are the three things I would like to see at the national and local level:

1. Bottle Bills: The logic behind these programmes is simple: you pay slightly more for your beverage, but get the money back when you return the can or bottle. It serves to disincentivise littering because people are less likely to throw away cash, and incentivise picking it up to claim back the deposit. From my experience in Chippenham, recyclable beverage containers make up approximately half of the litter by volume. That would be a lot of litter off the street if this were employed, and countries that use this have shown a drop in litter in general.

However, I can hear the chorus of disapproval already: Yes, we already have kerbside recycling. Yes, the infrastructure that needs to be put in place will be an initial expense. No, the packaging lobby does NOT want the UK to go down this route at all. But clearly, something has to be done or the problem will persist. The Bottle Bill website offers a more thorough discussion of the facts, figures, and myths surrounding these deposit schemes.

2. Enforced Fines: Many things in life come with fines to encourage the desired behaviour. Late with returning a library book or returning to your car beyond the allotted time? Receive a fine. Run a red light? Receive a fine. Throw rubbish from your vehicle while at a red light?

Fines for littering do exist and, indeed, there is currently talk of raising the fine to £150. I think that’s great … provided that it’s actually uniformly enforced across the country. If not, whether the fine is £150, £1500, or £15,000, it will not matter.

One of the reasons the enforcement of fines is so uneven is that some Councils fear a negative backlash; a few high profile cases where fines were enforced without flexibility or common sense have led to shying away from what seems to be a useful tool in the battle against litter. Related to this is changing the mindset that fines are just Councils after money. As discussed below, put the right spin on it and make it clear that money collected from fines will go towards ensuring a cleaner community for all.

3. Improved Binfrastructure: Something that comes up on a regular basis when talking to people about rubbish is the comment “There just aren’t enough bins”. Unless you’re speaking with government officials, in which case it’s then a matter of “There are enough bins, people just don’t use them!”

So what is the ideal frequency of bins? I don’t believe that there has been any scientific study into the matter, but according to factoids from Walt Disney World and Disneyland, Mr. Disney himself recommended that bins be placed no more than 30 feet apart. This is approximately how far people will carry litter before dropping it. I admit I’ve never measured the bin-to-bin distance when at a theme park, but this makes sense to me: with bins every 30 feet or so, you should always have one in your line of sight. There is no need to turn around or double back on to dispose of something nor walk any distance out of the way. Getting rid of rubbish is made quick and easy, and it also implicitly establishes the norm – rubbish goes in the bin.

In all honesty, I think the UK has gone beyond the point where just adding new bins will make a dent in the amount of litter because a new, unfortunate norm has been already been set: rubbish can go anywhere and (eventually) someone will clean it up. But smarter bins, smarter bin placement, and a healthy dose of education is a step in the right direction.

BUSINESS INVOLVEMENT

For the most part, companies do not cause litter directly. Instead, it is their customers and the consumers of the product who drop it once done. Yet it is the company’s name that is splashed across our streets and countryside. It is their cans and bottles that clog our waterways. Shouldn’t they have a modicum of social responsibility to try to prevent their packaging from blighting the country?

McDonald’s, for example, loves to point to their litter patrols as their contribution to tackling litter. Yet, as already mentioned, cleaning is not a longterm litter prevention strategy. Don’t get me wrong: it is currently necessary. But there are other things that companies both large and small could do to show that they are serious about stopping litter.

1. Ads: Large companies like McDonald’s and Coca-Cola have large marketing budgets. They know who their audience is and what message will reach them. It doesn’t have to be blatant. It’s doesn’t have to be in your face. If they can sell a burger or a fizzy drink, why not also subtly sell the idea of not littering?

2. Binfrastructure: I admit that many fast food shops or takeaways have bins directly outside their premises … which would be great if people ate their food in the doorway. They don’t. Instead, you can trace the trail of someone’s meal as they walk down the street: a napkin here. A wrapper there. Finally the bag and cup 100 metres or more down the road. Instead of continuing with the existing system, bin placement needs to be rethought to take human behaviour into account. And why not have sponsored bins that companies pay for?

3. Branding: Large companies tend to get the stick when it comes to littering as their brand is all over the packaging. Local takeaways and the like tend to be overlooked as their containers are generic and look the same. Why not encourage them to brand it with a label or similar? Following on from this, and emulating the idea behind the Bottle Bill, why couldn’t shops offer a small discount on a customer’s next meal if they bring back the branded container to dispose of properly?

4. Packaging: Something that companies have direct control over, and which could be easily changed, is the packaging itself. At the most basic level, it’s about ensuring that there is a clear anti-litter message, rather than the Tidy Man hieroglyph. For example, what about large text that reads “Littering carries a £150 fine; bin this properly and save your money to buy more Brand X”? It’s not exactly SMOKING KILLS, but it gets the point across. Or lottery scratch off tickets with the message “We hope you’re a winner, but if you’re not, don’t be a tosser – please bin this ticket.” With a little bit of creativity, an anti-litter message can be part of all packages and labels.

Another aspect is rethinking packaging in general. For example, is there a way to allow a pack to be opened without necessitating ripping part of it off, which simply creates two or more pieces of litter instead of one? Rethinking the design with litter prevention in mind could go a long way to reducing the current amount.

Litter on the dotted line: Packaging design like this almost seems to invite litter.

5. Cleaning Up: Finally, we come to cleaning. While I do not think it is the be all and end all of solutions as some would imply, it is important. It sets the tone for an area; after all, who wants to wade through rubbish to get to the shops? It is also part of the law that shops are supposed to keep within 100m of their premises clean, but much like the fines for littering, this is currently not enforced. Restaurants have employees initial a rota when they’ve cleaned the toilets; why not make regular clean ups part of the daily routine?

The current attitude of “It’s not my job, not my responsibility” needs to change. Instead, both independents and chain shops need to be sold on the idea that their exterior is part of the general cleanliness of their shop, of the impression they make to potential customers, and of taking pride in the community that they work in.

SOCIAL MARKETING

As the name implies, this is using marketing techniques to benefit a social cause, such as seen with campaigns to change behaviours such as smoking or seat belt use. In general, marketers ask what will encourage a certain audience to purchase a product. In the same way, the social marketer has to look at what motivational triggers make a group behave in particular way so that an intervention can be designed to change that behaviour or foster a new one.

At present, the reasons given for why people litter tend to be boiled down to the most simplistic terms. Litterers are lazy. They’re selfish. They’re thoughtless. And I admit I agree with a great deal of that. But by holding on to such basic motivations we lose the opportunity to look for solutions and to identify the trigger points that could be used to stop people from littering in the first place.

I asked a teenager at one of our local clean ups why he thought students his age littered. He answered, “They want to get on with their lives as quickly as possible.” This indicates that rubbish is viewed as a barrier, something that serves to slow one down. In many ways, this is a symptom of modern life, where the goal is to make things as “frictionless” as possible: we have contactless debit cards and one-click payment methods, travel and event tickets are delivered straight to our mobiles, and taxis can be ordered to our doorstep simply by pressing a button. Using a bin, especially one that’s out of the way, slows you down. Ditto carrying things that are no longer needed (it may also be messy). So the question may not be “How to stop people from littering?” but rather, “How do we make not littering the best option?” Questions such as this are necessary if we are to work with behaviour, not against it, and if educational programmes are to be developed that encourage a new generation to look after their environment and take pride in their community.

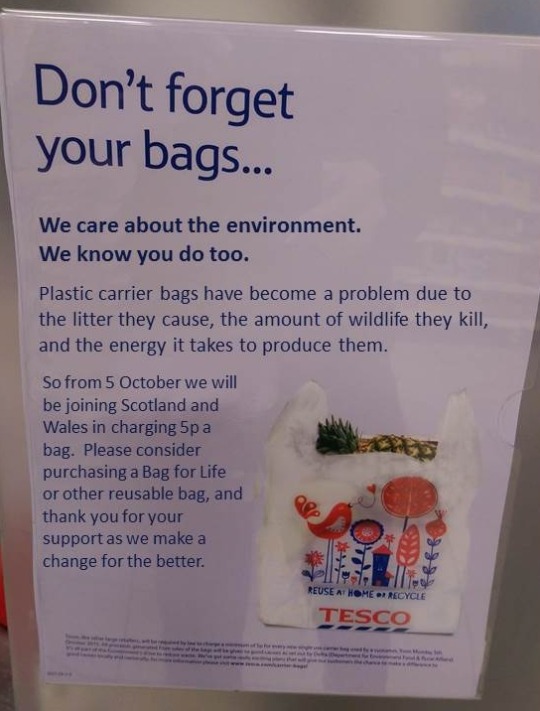

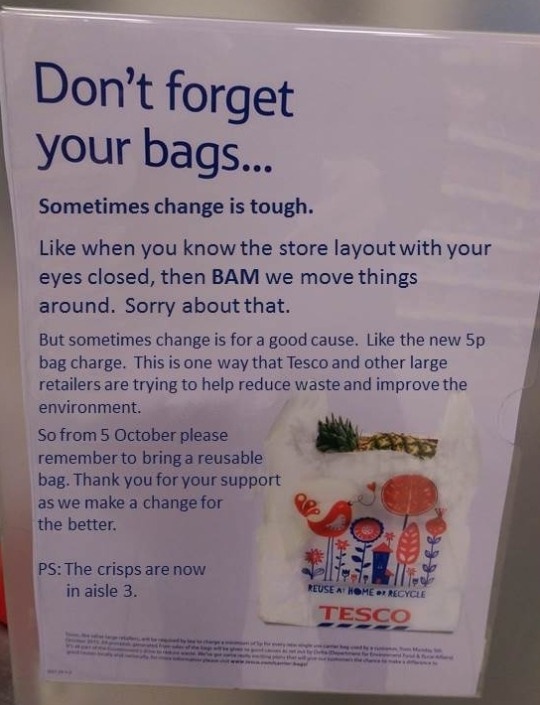

Related to marketing, “spin” is often seen as a four-letter word, something done by dodgy politicians with something to hide or companies who are trying to sell you something you don’t need. However, when done right, it can help change attitudes and encourage buy-in of the message you want to get across. The recent introduction of the 5p bag charge is a perfect example of how this wasn’t done. Instead of promoting the positives, explaining why it was necessary and what it hoped to accomplish, the signs I’ve seen in stores range from apathetic to bordering on hostile. Instead of doom and gloom, or even bluntly factual, messages need to be crafted carefully. From the signs below, it is clear that retailers did not buy-in to the bag charge.

Which message about the bag charge is more positive and therefore more likely to be received well by the public–the original above or the edited below?

Likewise, different approaches need to be taken with different segments of the audience. Advertisers have long known this. Are teenage boys affected by how their image is perceived? Then an anti-litter ad campaign around that subject stands a better chance of actually reaching them. What about middle-aged litterers? Perhaps they need to be reminded that as taxpayers their money could be better spent on other things.

Finally, the interventions that arise from this are not something that can be done once and the problem be considered as solved; this is partially what has gotten us into this mess in the first place. Instead, the message must be continually reinforced—at home, at school, when out and about—so that it becomes part of the culture and is considered a social norm.

CONCLUSION

What’s not in here in my rubbish manifesto: A reliance on Community Payback schemes to clean up litter. Because, say it with me, cleaning is not litter prevention. The other problem with these schemes is the message that it sends: “Picking up litter is a punishment … It is something that someone else does (not me!) … It doesn’t matter if I drop something, those people will pick it up.” We all must take responsibility for the problem of litter if we want to have any hope in solving it.

And this brings me to a wider point that tends to be overlooked in this discussion. Humans are social creatures and we unconsciously pick up messages all the time. With regards to litter, these are at best mixed and at worst contribute to the problem. Think about places such as cinemas, stadiums, and trains – what happens when people finish their food? They leave it at their seat for someone else to collect. Is it any wonder that many expect this same treatment elsewhere? Or look at the Royal Mail: I could follow our postie around the neighbourhood simply by following the trail of dropped rubber bands (which is such an issue that it has its own Wikipedia page). Or, my current bin-related bugbear, overflowing bins. The message this sends undermines everything that anti-litter groups are trying to do. It says: “Rubbish doesn’t matter.” It says: “In the bin? Out of the bin? Who cares!” It says: “Why bother?”

Yet very few things in life are actually insurmountable. It’s just a matter of how much time, energy, and money we are prepared to throw at them, or how willing we are to look at things from a different perspective. Either way, hasn’t there already been enough thought and discussion about the UK’s litter problem? Let’s work together and act to solve the problem.